>

A.L. Lloyd >

Songs >

The Oxford Tragedy

>

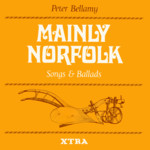

Peter Bellamy >

Songs >

The Prentice Boy

>

Waterson:Carthy >

Songs >

The Oxford Girl

The Miller’s Apprentice / The Prentice Boy / The Butcher Boy / Hanged I Shall Be / The Oxford Tragedy / The Oxford Girl / Wexford Town / The Wexport Girl / Ekefield Town / Ickfield Town

[

Roud 263

/ Song Subject MAS145

; Master title: The Miller’s Apprentice

; Laws P35

; G/D 2:200

; Ballad Index LP35

; VWML HAM/2/8/20

; Bodleian

Roud 263

; GlosTrad

Roud 263

; Wiltshire

105

, 586

; MusTrad DB11

; DT CRUELMIL

, HANGEDBE

; Mudcat 28033

, 97739

; trad.]

Fred Hamer: Garners Gay Maud Karpeles: Cecil Sharp’s Collection of English Folk Songs Ewan MacColl, Peggy Seeger: Travellers’ Songs From England and Scotland John Morrish: The Folk Handbook Roy Palmer: Everyman’s Book of English Country Songs Frank Purslow: The Wanton Seed Steve Roud, Julia Bishop: The New Penguin Book of English Folk Songs Stephen Sedley: The Seeds of Love Elizabeth Stewart, Alison McMorland: Up Yon Wide and Lonely Glen Sam Richards and Tish Stubbs: The English Folksinger

E.J. Moeran collected the grim murder ballad Hanged I Shall Be in October 1921 from ‘Shepherd’ Taylor of Hickling, Norfolk. Roy Palmer printed it in 1979 in his Everyman’s Book of English Country Songs.

Taylor’s Kentucky Boys recorded Maxwell Girl on 26 April 1927 in Richmond, Indiana and Ernest V. Stoneman recorded Down on the Banks of the Ohio for Edison on 25 April 1928 in New York City. Both recordings were included in 2015 on the Nehi anthology of British songs in the USA, My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean. Steve Roud noted:

Another of the ‘murdered sweetheart’ ballads which originated, and was widely sung, in England, but which reached new heights of popularity in North America, where scores of versions were collected from traditional singers. As The Berkshire Tragedy or Wittam Miller it first appeared in a mid-18th century garland, but later traditional versions owe more to a much cut down version which broadside printers first issued about 1800. It was widely believed to be based on a true story, and there are two contenders in broadsides from the late 17th century that might support this theory, but as these themselves cannot be shown to be actually ‘true’, the question remains to be decided.

Louisiana Lou sang The Export Girl in a recording made on 4 December 1933 in Chicago, Illinois that was included in 2018 on the Musical Traditions anthology of Anglo-American songs and tunes, A Distant Land to Roam. Mike Yates and Rod Stradling noted:

MacColl and Seeger quote an American source who says that the villain in this song was a John Mauge, who was hanged at Reading, Berkshire, in 1744. But, we know that The Export Girl comes originally from a long 17th century ballad The Berkshire Tragedy, or, The Wittam Miller, a copy of which may be seen in the Roxburgh Collection (vol. viii p.629), and it may be that Mauge’s name came to be associated with the earlier ballad because of the similarity of his crime. Later printers tightened the story and reissued it as The Cruel Miller, a song which has been collected repeatedly in Britain and North America (where it is usually known as The Lexington/Knoxville Girl).

Other recordings: Mary Ann Haynes (Sussex) - MTCD320; Mary Delaney (London, ex Co Tipperary) - MTCD325-6; Harry Cox (Norfolk) - TSCD512D; The Blue Sky Boys (NC) - JSP 7782B; Kilby Snow (VA) - Field Recorders’ Collective FRC205.

Cecilia Costello from Birmingham sang The Wexford Murder to Maria Slocombe and Patrick Shuldham-Shaw on 30 November 1951. This BBC recording 17035 was included in 1975 on her eponymous Leader album Cecilia Costello and in 2014 on her Musical Traditions anthology Old Fashioned Songs. Rod Stradling noted:

The killing of a woman in order to conceal her seduction and pregnancy is a frequent motif in songs. In The Cruel Ship’s Carpenter the murder is discovered and punished by supernatural agency. Mrs Costello’s song, which is similar to a number of other gory nineteenth century broadsides, has a good melodramatic denouement brought about by the victim’s classic statement: “I was murdered here last night”.

Roud has only two named singers of this ballad in England, and just one in Ireland—so the Irish names and places in Cecilia’s song might appear to be unusual; most of the British entries are from Scotland, where the title The Longford Murder is most common.

There are only 38 entries for this ballad and, while 15 refer to sound recordings, only two of these have ever been published; and neither has ever appeared on CD.

A.L. Lloyd sang this ballad as The Oxford Tragedy in 1956 on his Riverside LP English Street Songs. He was accompanied by Alf Edwards on concertina. All tracks from this album were included in 2008 on his Fellside compilation Ten Thousand Miles Away. He noted:

Perhaps this is the most important of all murder ballads carried across England by the street singers. At least, a vast number of pieces of ballad journalism have taken it for a pattern during the last two and a half centuries. The original comes from a broadside from the end of the 17th Century called The Wittam Miller (Wittam is a village near Oxford). Most of the 19th Century stall-ballad publishers printed a version of this form favourite, which was probably the parent ballad to the American murder ballads The Knoxville Girl and Florella.

Jeannie Robertson of Aberdeen sang The Butcher Boy, in a recording made at her home in 1955, on her 1956 Riverside album Songs of a Scots Tinker Lady. Hamish Henderson noted:

This murder ballad, with its uneasy psychological undertones, is sometimes known as The Murder of Sweet Mary Anne. It appears to derive from a 17th century broadside in which the murdering lover is a miller. In the United States, the ballad is best known as The Lexington Murder or The Knoxville Girl, and has undoubtedly been the inspiration for several other murder ballads. In the form sung here, it is still very popular in Scotland.

Another recording of Jeannie Robertson made by Alan Lomax in 1953 can be found on the anthology Fair Game and Foul (The Folk Songs of Britain Volume 7; Caedmon 1961; Topic 1970). The booklet noted:

American listeners, who are accustomed to the brisk measures of Pretty Polly or the start directness of The Knoxville Girl, may be surprised to encounter a slow and highly ornamented Scots variant of this familiar ballad. It is the favourite British remake of The Cruel Ship’s Captain theme and might be called the classic British murder ballad, in the same sense that Omie Wise or Pretty Polly are the central ballads of the Southern American tradition. In most English variants, the murder weapon is a stick cut from a hedgerow, as in Harry Cox’s version about Ekefield Town

As we’re a-walking and a-talking

Of things that grew around,

I took a stick from out of the hedge

And knocked that fair maid down.Perhaps the most dramatic verses occur in a version recorded from a gypsy woman in Suffolk:

It was about three weeks afterwards

When that pretty fair maid were found

Come floating down by her own mother’s door

On, near Oxford Town.

Harry Cox from Catfield, Norfolk, sang this ballad on 19 July 1956 to Peter Kennedy for the BBC recording 22915, where it was called Ekefield Town. This recording was also included in 1965 as The Prentice Boy on his eponymous EFDSS album Harry Cox. Another recording made by Mervyn Plunkett on 12 June 1960 was included again as Ekefield Town in 2000 on Cox’s Topic Records 2 CD anthology, The Bonny Labouring Boy. Steve Roud noted:

Quite widely collected in Britain by Cecil Sharp and his contemporaries, and in the repertoire of several well known post-war singers such as Cecilia Costello, Jeannie Robertson, and Phoebe Smith, this song was even more well-known in North America, where dozens of versions (under such titles as The Wexford Girl or The Lexington Miller) have been noted and published. As pointed out by Laws (American Balladry from British Broadsides, 1957), in a chapter on “ballad recomposition”, the original text appeared in the mid-18th century as The Berkshire Tragedy or The Wittam Miller, and has since undergone not simply the vagaries of oral tradition, but deliberate re-composition, apparently on more than one occasion. Comparing Harry’s with the Original, his is severely truncated and avoids the wordiness of 18th century texts, but it includes many of the most telling details, such as the stake from the hedge, and the dragging by the hair. Nevertheless, the omission of the original motif of pregnancy leaves the murder motiveless in Harry’s version, which heightens either the song’s stark horror, or the sordidness, according to the listener’s own viewpoint.

Ewan MacColl sang The Butcher Boy in 1956 on his Riverside album Scots Street Songs. He noted:

This is another variant of the popular broadside murder ballad found more frequently under the name of The Gosport Tragedy, The Oxford Murder, and The Wittan Miller and from which most American murder ballads seem to stem. This version is from the singing of Jeannie Robertson.

Phoebe Smith of Woodbridge, Suffolk sang The Oxford Girl to Peter Kennedy on 8 July 1956. This BBC recording 23099 was included in 2012 on the Topic anthology of ballads sung by British and Irish traditional singers, Good People, Take Warning (The Voice of the People Volume 23). She also sang The Wexport Girl to by Paul Carter and Frank Purslow in her home in Melton, Woodbridge, Suffolk in 1969. This recording was included a year later on her Topic LP Once I Had a True Love on which Frank Purslow noted:

One of the most powerful and best known of our traditional murder ballads, also found as The Berkshire Tragedy, The Oxford/Wexford Girl, The Cruel Miller etc., it seems to have derived from the opening verses of a broadside of 1650 describing William Grismond’s murder of his sweetheart at Lainterdine, Herefordshire on March 12th of that year. The verses were subsequently pruned, recomposed and reprinted several times, coupled with later crimes of a similar nature, including that committed by John Mauge, for which he was hanged at Reading in 1744. He apparently lived at Wytham, just outside Oxford, but over the Berkshire border, and this crime gave rise to the most influential of the broadside versions of the text entitled The Berkshire Tragedy; or, The Wittam Miller. Versions of the story were still being printed late in the last century.

Enoch Kent sang The Butcher Boy in 1962 as title track of his Topic EP The Butcher Boy and Other Ballads. All tracks from this EP were reissued in 1965 as part of the Topic LP Bonny Lass Come O’er the Burn. Norman Buchan noted:

Though Francis James Child characterised the broadside ballads as ‘veritable dungheaps’ he conceded the occasional ‘moderate jewel’. This one, ennobled by a splendid tune, is a good deal more than that. It contains little of the conventional trappings of the professional product—no last dying speech, no explanation for the murder, usually pregnancy, no ‘take warning by me’. Indeed it shows much of the bare economy of story line of our classical ballads and is obviously moulded by a community in which the great tradition was still very much alive. It will come as no surprise, therefore, that Enoch learned it from perhaps the greatest living expression of that tradition, Jeannie Robertson.

Queen Caroline Hughes sang The Prentice Boy to Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger in 1963 on 1966. This recording was included in 2014 on her Musical Traditions anthology Sheep-Crook and Black Dog. Another recording of Caroline Hughes singing The London Murder in her caravan in Blandford, Dorset on 19 April 1968 to Peter Kennedy was included in 2012 on the Topic anthology of songs by Southern English Gypsy traditional singers, I’m a Romany Rai (The Voice of the People Volume 22). Rod Stradling noted on her MT anthology:

A very well-known song indeed, with 355 Roud instances, 98 of which are sound recordings. MacColl and Seeger quote an American source who says that the villain in this song was a John Mauge, who was hanged at Reading, Berkshire, in 1744. But, we know that Waxford Town comes originally from a long 17th-century ballad The Berkshire Tragedy, or The Wittam Miller, a copy of which may be seen in the Roxburgh Collection (vol. viii p.629), and it may be that Mauge’s name came to be associated with the earlier ballad because of the similarity of his crime. Later printers tightened the story and reissued it as The Cruel Miller, a song which has been collected repeatedly in Britain (59 instances) and North America (228 instances—where it is usually known as The Lexington/Knoxville Girl).

Both Laws and Roud differentiate between the two versions, giving Roud 263, Laws P35 for this one and Roud 409, Laws P24 for the other—usually known as The Butcher Boy. However, since Roud includes 318 and 275 examples respectively, it must be clear that there will be many versions which, like Caroline’s above, fall into the grey area between them.

Paddie Bell sang The Butcher Boy, accompanied by Martin Carthy on guitar, in 1965 on her EMI/Waverley album Paddie - Herself. W. Gordon Smith noted:

Another Newfoundland variant of a song that comes to us in many guises. Originally a broadside ballad, it is a masterpiece of condensation and a superb example of a poetically tragic human situation contained in the minimum of words. Paddie adapted the Newfoundland air to suit her own purposes.

Sarah Porter sang Down by the Deep River Side in 1965 at The Three Cups, Punnetts Town. This recording made by Brian Matthews was included in 2001 on the Musical Traditions anthology of songs from Sussex country pubs, Just Another Saturday Night. The album’s booklet noted:

Although this song looks like a version of The Oxford Girl, I’m told that it’s actually a version of Floating Down the Tide (Roud 1414) which is derived from a quite different ballad. I’m sure the distinction would be lost on most of its singers.

Both songs are very widespread with a total of 240 entries in Roud—the earliest of which is dated 1796—though considerably more than half of them are from the USA and Canada. In England, at least, they are now very much the preserve of Travellers.

They go by a bewildering array of different names: The Berkshire/Worcester Tragedy, The Bloody/Cruel Miller, The Butcher/’Prentice/Miller/Collier Boy, Poor Nell, Johnny McDowell, The Lexington Murder … And then there’s the staggering range of place names: Boston, Camden, Coleraine, Ekefield, Expert, Export, Knoxville, Lexington, London, Noel, Oxford, Shreveport, Waco, Waterford, Waxford, Waxweed, Waxwell, Wexford, Wexport … all relating to the Girl, Town or City of the action.

What this tells us, I think, is that these are songs which—perhaps more than any others—have the ability of sounding like a story you already know. It’s the stuff of Urban Legend—songs of which the older singers would so often claim, “My father knew the people involved!” It’s pretty dispiriting to realise that the murder of a pregnant girl by the man who made her so, was a commonplace.

I still think that Sarah Porter’s song is of the Oxford Girl family as the girl gets murdered and doesn’t drown herself.

Peter Bellamy sang The Prentice Boy in 1969 on his second LP, Fair England’s Shore. He also sang it on 17 November 1968 at the Young Tradition concert at Oberlin College, Ohio, that was released in 2013 on their Fledg’ling CD Oberlin 1968. He noted on the first album:

The Prentice Boy is just one form of what must be one of the most widely-spread song plots in the world. This version comes from Norfolk, and has been collected under this title several times in that country; but listen to any version of The Oxford Tragedy or The Butcher Boy—or any of the American Omie Wise / Pretty Polly songs, and you find the same story. Perhaps it was always happening!

Jack Smith sang How Could I Marry on 5 November 1969 at the King’s Head Folk Club in Milford, Surrey. This recording was included in 2012 on the Musical Traditions anthology King’s Head Folk Club of traditional performers at this London Folk Club 1968-1970. Rod Stradling’s notes are similar to those on Caroline Hughes’ MT anthology.

Shirley Collins sang the both tender and cruel murder ballad The Oxford Girl unaccompanied in 1970 on her and her sister Dolly’s album Love, Death & the Lady. She noted:

From the singing of the fine Suffolk singer Phoebe Smith—a woman of great presence, whose stately, dignified style affected me quite profoundly. I am always struck by the tenderness underlying this murder ballad, which strangely doesn’t seem inappropriate.

Lizzie Higgins sang The Butcher Boy to Ailie Munro in Aberdeen in 1970 (SA1970.22.B4). This recording was included in 2006 on her Musical Traditions anthology In Memory of Lizzie Higgins. Rod Stradling noted:

Despite its title, this is actually a version of the Oxford Girl, and thus really quite rare in Scotland; Roud has only 5 instances from here, and one of those is from Orkney. Most of the other 290 examples are from England or North America, but of the 75 sound recordings, only those by Harry Cox - The Bonny Labouring Boy; Mary Ann Haynes - Here’s Luck to a Man …; Mary Delaney - From Puck to Appleby; The Carter Family - Bear Family BCD 15865 In the Shadow of Clinch Mountain; and the Blue Sky Boys - BCD 15951 The Sunny Side of Life seem to be available on CD.

Gavin Greig considered that such ‘Ballads of Murder and Execution’ had been imported to his area via broadsides emanating from the Emerald Isle where they were highly popular. Lizzie learned it from her mother [Jeannie Robertson], but performed it infrequently.

Martin Carter sang The Cruel Miller in 1971 on his Traditional Sound album Someone New

The Union Folk sang The Butchers Boy in 1971 on their Traditional Sound album Waiting for a Train

Roger Grimes sang The Miller’s Apprentice unaccompanied in 1972 on Nott’s Alliance’s Traditional Sound album The Cheerful ’Orn. They noted:

One of the many versions of the most famous English murder ballad. This particular set was noted down originally by Hammond from Joseph Elliott of Todber in Dorset in 1906 [VWML HAM/2/8/20] . (Frank Purslow calls it The Prentice Boy in his book of the songs.) Related versions were reprinted many times by the stall-ballad publishers in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Mary Ann Haynes of Brighton, Sussex, sang Wexford Town in a recording made by Mike Yates in between 1972 and 1975 that was released in 1976 on the Topic album of country singers from the South, Green Grow the Laurels and in 2003 on the Musical Traditions anthology of Gypsy songs and music from South-East England recorded by Mike Yates, Here’s Luck to a Man …. Mike Yates noted on the first album:

Wexford Town comes originally from a long 18th-century ballad The Berkshire Tragedy, or The Wittam Miller which is included in the Roxburgh collection. Later printers tightened the story and issued it as The Cruel Miller, which has been repeatedly collected not only in Britain but in North America as well, where it is known as The Lexington (or Knoxville) Girl.

Martin Carthy sang this song with the title Hanged I Shall Be on the Albion Country Band’s album Battle of the Field. This album which was recorded in 1973 but wasn’t published before 1976. A May 1973 live recording for the BBC appeared on The Albion Band: The BBC Sessions, released in 1998 after only a 25 year wait! This may also be the version on their 2010 Talking Elephant compilation Vintage II: On the Road 1972-1980.

Mary Delaney from Co. Tipperary sang Town of Linsborough to Jim Carroll and Pat Mackenzie in between 1973 and 1985. This recording was included in 2003 on the Musical Traditions anthology From Puck to Appleby. Carroll and Mackenzie noted:

According to John Harrington Cox, The Wittam Miller is said to describe a murder that took place in 1744 in Reading, in Berkshire, though there are two broadsides dating from sixty and forty-four years earlier with similar titles. An excellent account of how this has been shaped by time and tradition from a long, ungainly broadside entitled The Berkshire Tragedy or The Wittam Miller, to the concise piece that it has become, is to be found in Malcolm Laws’ American Balladry from British Broadsides.

The ballad has travelled widely through Britain, Ireland and particularly America, where it proved hugely popular with country singers and has given rise to other songs on the same theme, for instance Down by the Willow Garden and Omie Wise.

It has been found under many titles, which often identify the place where the murder was supposed to have been committed: The Wexford, Waterford, Oxford, or Lexington Girl to name a few. The murderer has been given a variety of occupations: butcher, printer, miller, or simply apprentice.

Mary’s version is fairly typical of many of the Irish and American texts with the exception of the last line, which is somewhat confusing. In most texts the murderer is found guilty and hanged, but here Mary has used the last line of Father Tom O’Neill (Roud 1013, Laws Q25), an incomplete eight verse set of which she has in her repertoire. In another recording we made of this, she sang as her two last lines:

His sentence was for his life and then he’d have to settle down,

For no more was said with the treasury only he did go down.She was unable to explain the meaning of this and it is possible that she had extemporised it.

Linsborough is possibly Lanesborough in Co Longford.

Ref: American Balladry from British Broadsides, G Malcolm Laws Jnr, American Folklore Society, 1957; Folk Songs of the South, John Harrington Cox, Harvard Univ Press, 1925.

Amy Birch sang He Pulled a Dagger in a recording made by Sam Richards and Tish Stubbs in 1974-80 that was released in 1981 on Folkways’ An English Folk Music Anthology. Sam Richards noted:

Some collections call this The Wexford Girl (as in Laws P35), others The Prentice Boy. Whatever, it is a remarkably tenacious song in tradition, and is said to date back to an actual event in Berkshire in 1744.

Early broadside texts are long and involved, but the life of this song in folk tradition has made it more economical as Laws points out in some detail.

Amy Birch has a fantastically powerful voice—hard-edged, nasal, and quite imposing to listen to, especially in the confines of a caravan. Her slow, deliberate style is typical of many travellers, especially women. Her commitment to a song is total. She uses the occasional decorative sobs and slides used by many modern travellers. Some commentators have regretted this as an influence from Country And Western music, which is popular amongst travellers. In Amy’s case it may well derive from one of her favourite recorded singers, Bessie Smith—anything but Country And Western.

Perhaps oddly for such a commanding singer, Amy is a little shy of performing for strangers, and singing is very much a family affair.

Isabel Sutherland sang The Butcher Boy in 1974 on her eponymous EFDSS album Isabel Sutherland. She noted:

This broadside ballad I learned from the singing of Enoch Kent when he stayed with us when he first came to London in 1960.

Cathy LeSurf sang The Prentice Boy in 1983 on Oyster Band’s Pukka album English Rock ’n’ Roll: The Early Years 1800-1850.

Sara Grey and Ellie Ellis sang Knoxville Girl in 1984 on their Fellside album Making the Air Resound. They noted:

It’s a descendant of the British ballad, Wexford Girl, whose genealogy runs Oxford Girl, The Cruel Mother, Lexington Girl, Export Girl (from Colonial America), and finally, Knoxville Girl. This Ozark version comes from the singing of Wilma, Betty and Dale Copeland. Early versions of the song made it clear that the girl was pregnant, and was killed by her lover, who refused to marry her. This detail was later dropped. 19th century America didn’t sing about pregnancy—the subject is still taboo amongst mixed audiences of Ozark Mountain people. The song clearly shows that women were often victims of society in our history—and some of that kind of victimisation still occurs, after all this time.

Bill House of Beaminster, Dorset sang The Wexford Murder to Nick and Mally Dow on 12 April 1985. This recording was released in the same year on the Old House cassette anthology of traditional folksongs collected by Nick and Mally Dow, Gin and Ale and Whisky.

Andy Turner sang The Prentice Boy in 1995 on the Mellstock Band’s album Songs of Thomas Hardy’s Wessex. The song was collected by Henry Hammond from Joseph Elliott of Todber in Dorset [VWML HAM/2/8/20] , with some additional words here as noted by Thomas Hardy himself. He returned to this song 25 years later, singing it as the 13 June 2021 entry of his project A Folk Song a Week.

Ray Fisher learned The Butcher Boy from the singing of Jeannie Robertson and sang it in 1999 at the Folk Festival Sidmouth.

Elizabeth Stewart sang The Butcher’s Boy in 2004 on her Elphinstone Institute anthology Binnorie. Thomas A. McKean noted:

The Butcher Boy, widely distributed throughout the English-speaking world, seems to be of fairly recent origin, though the theme, floating verses, and some motifs are clearly longstanding in tradition. Elizabeth’s version, from her mother, Jean, is one of the few containing the crucial fact that the butcher boy has been with another woman; in some cases a pregnancy is involved. Other versions have the lad disposing of his sweetheart in order to marry a woman of higher status. The song is often assumed to be a conflation of two (some think four) separate songs, due to the shift in perspective between first and third persons; others consider it to be a single song, of American origin, e.g. MacEdward Leach, The Ballad Book (New York: Barnes, 1955), p.737.

Another Elizabeth Stewart recording from the Fife Traditional Singing Festival, Collessie, Fife in May 2005 was released in the following year on the festival compilation For Friendship and for Harmony (Old Songs & Bothy Ballads Volume 2) on which Peter Shepheard noted:

This widely popular murder ballad appears to derive from a text first published in the early 1700s under the title The Berkshire Tragedy or The Wittam Miller. This broadside text was adapted, amended and republished many times between 1780 and 1850 and the song has been widely collected in Britain and the USA under many different titles: The Miller’s Apprentice, The Prentice Boy, The Oxford Miller, The Wexford Miller (in Ireland), and The Butcher Boy (in Scotland and USA). Elizabeth has a particularly complete version with elements of the story often absent elsewhere.

Norma Watersons sang The Oxford Girl a much more straightforward murder story in 2005 on Waterson:Carthy’s fifth album, Fishes & Fine Yellow Sand. Martin Carthy noted:

With Liza’s lead we sort of made up the melody for The Oxford Girl for Norma so sing from bits and pieces and personally I think that the result is rather good. In some sets of the song the words, towards the end, portray a full scale vision of the fires of hell at his bed foot, but it loses nothing by being ever so slightly more subdued.

John Kirkpatrick re-introduced the girl’s pregnancy to the story, renamed the song to Ickfield Town, and sang it in 2005 on the Fellside celebration of English traditional songs and their American variants, Song Links 2. Sheila Kay Adams sang the corresponding American variant, Knoxville Town. The sleeve notes commented:

This song, most commonly known as The Oxford Girl or The Cruel or Bloody Miller, tells in the first person the story of a young man who murders his sweetheart. In some versions, the girl is pregnant, and the story is often tenderly told—“I gently knocked her down” and “I took her down to the river’s edge and gently throwed her in”. And generally the man shows remorse, or is it just a ploy to save himself from the gallows?

John Kirkpatrick calls his version Ickfield Town, and it’s based on a version (Ekefield Town) from Harry Cox (born 1885) of Catfield, Norfolk. One of the greatest of the English traditional singers, farm worker Harry had a large and fine repertoire of songs, which he sang in his natural Norfolk dialect with a great deal of grace and beauty. John has added further words from two remarkable gypsy women, Phoebe Smith and Cecilia Costello.

Jackie Oates and Alasdair Roberts sang The Butcher’s Boy in 2009 on her album Hyperboreans. This track was also included in 2010 on the Leigh Folk Festival compilation Horses & Hangings, Homicide & Hellfire. She noted on her album:

Learnt from the singing of Elizabeth Stewart via a compilation of Scottish songs put together by Alasdair Roberts. Of all the murder ballads that I’ve come across, I have found this the most graphic and yet the most compelling.

Jon Boden sang The Prentice Boy as the 1 September 2010 entry of his project A Folk Song a Day. He also sang it in 2024 on his Hudson album with the Remnant Kings, Parlour Ballads. This video shows Jon and The Remnant Kings performing The Prentice Boy at the A Folk Song a Day Midsummer Concert at Cecil Sharp House, London, on 23 June 2011:

Jess and Rich Arrowsmith sang Hanged I Should Be on their 2012 album Customs & Exercise. They noted:

There are countless versions of this blood-thirsty ballad, which first appeared in broadside form as The Berkshire Tragedy or, The Wittam Miller in the late 18th century. This set of lyrics owes much to The Albion Country Band’s 1973 adaptation, which in turn is a variant of the words collected by E.J. Moeran from a Norfolk man in 1921 and published in Roy Palmer’s Everyman’s Book of English Country Songs. The tune, however, is a brand new one. The story itself wouldn’t be out of place on the front cover of the Daily Mail, a sad reminder that senseless violence is no modern invention.

Ewan McLennan sang Butcher’s Boy in 2012 on his Fellside CD The Last Bird to Sing. He noted:

I’ve never usually been drawn to murder ballads; but on hearing the brilliant version of this song by Enoch Kent I was drawn to this broadside. What came before our story here and what the motivation was remains a mystery.

Faustus sang Prentice Boy in 2013 on their CD Broken Down Gentlemen. They noted:

Noted from Joseph Elliott of Todber, Dorset in September 1905 by the Hammond Brothers [VWML HAM/2/8/20] , and published in Frank Purslow’s The Wanton Seed.

The accompanying melody is the Cotswold morris dance tune Highland Mary.

Rosie Upton sang The Butcher Boy in 2014 on her CD Basket of Oysters. She noted:

I heard the late Isabel Sutherland sing this many years ago and knew I had to learn it. It’s been in my repertoire for more than 40 years and I still find it chilling. A powerful song that tells everything about the abusive force that a man can wield over a woman. We don’t know why he killer her and she has no voice. It is left for the listener to imagine. Did he rape her, was she pregnant, was he jealous or was it revenge? Why do we relish such appalling stories?

Olivia Chaney sang The Oxford Girl in 2015 on Earth Records’ anthology celebrating Shirley Collins, Shirley Inspired and in this 2014 video from the forthcoming movie The Ballad of Shirley Collins:

David Stacey sang Wexford Town in 2015 on his Musical Traditions album Good Luck to the Journeyman. Again, Rod Stradling’s notes are similar to those on Caroline Hughes’ MT anthology.

Kristi Hedtke and Corbin Hayslett sang Knoxville Girl on the 2017 Appalachian ballad tradition anthology Big Bend Killing.

Reg Meuross and Harbottle & Jonas sang The Oxford Girl on their 2021 album Songs of Love & Death. Meuross noted:

Oxford Girl I knew from the American duo, The Louvin Brothers’ version, Knoxville Girl.

Lyrics

Louisiana Lou sings The Export Girl

I fell in love with an Export girl

With brown and rolling eyes

I asked her if she’s marry me

She said she never denied

“Come on, come on and take a walk

And talk about it now

Then talk about our wedding day

And when it’s going to be”

They walked and talked

They walked and talked

‘Til they came to level ground

Then he picked up a (seasoned/cedar) stick

And knocked that fair maid down

“O Billy, O Billy, don’t you kill me now

For I’m not prepared to die”

He beat on the fair maid more and more

Until she fell to the ground

He took her by her lily white hand

And he swung her round and round

And took her to some deep water sea

And threw her in to drown

He went to his mother’s house

It was the middle of the night

When he found her sleeping there

She woke up in a fright

“Billy, O Billy, what have you done

To blood your hands and clothes?”

He answered in a solemn tone

‘Been bleeding from my nose’

“O mother dear bring a towel

For my aching head

Then mother give me a candle stick

To light me up to bed”

Two months, four months, six months from then

That Export girl was found

Floating down that little mill stream

Right through that Export Town.

They’ve got me now in an Export jail

An awful death to die

They’re going to hang me by my neck

Between the earth and the sky.

Cecilia Costello sings The Wexford Murder

Spoken: My father come from County Roscommon, Ireland. I was … being the youngest he was very strict with me, and he used to say when I come out of school … I’d say to him: “Dad. I’ve been learning a song about a farmer—All the day long in the cornfields so weary, father has toiled of the heat of the sun”—I used to be telling my father this. Then my father’d say: “I know summat like that, come here”. And he’d get me between his legs and he’d start. And he learned me all the songs as he knowed while he lived in Ireland. And there you are, as I grew older I never forgot ’em. And as I grew … the first time my baby could walk, my oldest, I started—he’s sixty—and I kept on with every one I’ve had. Well I used to sit and tell these children all what I went through when they were little. And then again they’d say … come from school and they’d say: “Tell us another song what your father used to learn”. And I learnt them, see.

You young and old, I now make bold,

I’ll hope you’ll lend and ear

For it is as cruel a murder

As ever you did hear

It’s all about a young fair girl,

Her age was scarce sixteen

Her beauty bright was my delight

‘Til Satan a-tempted me.

Now this girl she being a servant girl

And I a farmer’s son

And from the county of Wexford

Convenient to Tyrone

I courted her in private

‘Til I got her beguile

And then to take her precious life

I planted in my mind.

So I sent for her one evening

And soon she came to me

I said, “Dear Jane, now don’t complain,

But to Wexford we will go”

I said, “Dear Jane, now don’t complain,

To Wexford we will go

And there we will get married

And I’m sure no one will know.”

So it being so late they both stepped out

Across the country;

It would draw tears down from your eyes

The talk she said to me

I told her I was going to murder her

And this I made reply

Saying, “Jane O’Riley you must go,

For it’s here you’ve got to die.”

“Oh James, look on your infant dear,

And do spare me my life,

And don’t commit a murder

Such a dark and dreary night

For to God I’ll promise on my knees

If you’ll spare me my life

I’ll never go nor bother you

Nor ax to be your wife.”

But all she said it was in vain

And he gave her a mortal blow

With his heavy loaded whip

He left her in her gore

Her blood and brain they flew like rains,

Her moans would pierce your heart

I thought I had her murdered

Before I did depart.

But she being alive next morning

Just by the break of day

There was a shepherd’s daughter

That came along that way

She saw the girl lie in her blood

And drew to her relief

Saying, “I was murdered here last night,

Will you bring me the priest?”

Now the priest and doctor was sent for,

Likewise the police at large

They soon got information

When she had told my name

They soon got information

When she had told my name

And I was bound a prisoner

And locked in Wexford gaol.

So me name it is James Brennan

And my life I now must part

For the murder of young Jane Riley

I’m sorry to the heart

I hope the Lord will pardon me

All on my judgement day

And when I’m on my dismal track,

Good Christians, for me pray.

Jeannie Robertson sings The Butcher Boy

His parents gave him good learning,

Good learning they gave unto him,

For they sent him to a butcher’s shop

For a butcher boy to be.

It was there that he met with a fair young maid

With dark and a rolling eye,

And he promised for to marry her

On the month of sweet July.

For he went up to her mother’s house

Between the hour of eight and nine,

And he asked her for to walk with him

Down by the foaming brine.

But they walked it east and they walked it west

And they walked it all alone,

Till he pulled a knife from out of his breast

And he stabbed her to the ground.

She fell upon her bended knees

And for mercy she did cry,

“Owen Barry, dear, don’t murder me

For I’m not prepared to die.”

But he took her by the lily-white hand

And he dragged her to the brim,

And with a mighty boundward push

He pushed her body in.

He went home till his own mother’s house

Between the hour of twelve and one,

But little did his mother think

What her only son had done.

He asked her for a handkerchief

To die around his head,

And he asked her for a candle-light

For to show him up to bed.

But no sleep, no rest, could this young man get,

No rest he could not find,

For he thought he saw the flames of hell

Approaching his bedside.

But the murder it was soon found out

And the gallows was his doom.

For the murder of sweet Mary Anne

That lies where the roses bloom.

Harry Cox sings Ekefield Town

As I was fast bound ’prentice boy, I was bound unto a mill,

And I served my master truly for seven years and more,

Till I took up a-courting with the girl with the rolling eye,

And I promised that girl I’d marry her if she would be my bride.

So I went up to her parents’ house about the hour of eight,

But little did her parents think that it should be her fate.

I asked her if she’d take a walk through the fields and meadows gay,

And there we told the tales of love and fixed the wedding day.

As we were walking and talking of the different things around,

I drew a large stick from the hedge and knocked that fair maid down.

Down on her bending knees she fell and so loud for mercy cried,

“O come spare the life of a innocent girl, for I am not fit to die.”

Then I took her by the curly locks and I dragged her on the ground

Until I came to the riverside that flowed through Ekefield town.

It ran both long and narrow; it ran both deep and wide,

And there I plunged this pretty fair maid that should have been my bride.

So when I went home to my parents’ house about ten o’clock that night.

My mother she jumped out of bed all for to light the light.

She asked me and she questioned me, “O what stains your hands and clothes?”

And the answer I gave back to her, “I’ve been bleeding at the nose.”

So no rest, no rest, all that long night; no rest, no rest, could I find.

The fire and the brimstone around my head did shine,

And it was about two days after this fair young maid was found,

A-floating by the riverside that flowed through Ekefield town.

Now the judges and the jurymen on me they did agree,

For murdering of this pretty fair maid so hanged I shall be.

O hanged, O hanged, O hanged I shall be,

For murdering of this pretty fair maid, so hanged I shall be.

Caroline Hughes sings The Prentice Boy

There was once a man he lived in London Town,

Well, he had such a joys for while,

If he spent one pound he spent ten,

It were all for the want of a wife.

O then Jackie went a-walking with his own true love,

O strange thoughts came into Jackie’s mind;

O to murder his own true love

And for slighting in her poor life.

She said, “Jack, my dear, don’t murder me,

For I is not fit to die;

O Jack, my dear, don’t murder me,

‘Cause I’m improving a child by thee.”

O he pulled a stick out of the hedge,

And he beat her across the head;

And the blood came trinklin’ from that innocent girl,

It come trinklin’ all down her sides.

O for he catched hold of her curly locks,

And he dragged her to the ground;

He dragged her to some riverside

Her poor body lays there to drown.

O he went alone to his master’s house,

At eight o’clock at night;

While they come down to let him in

By the strivings of candlelight.

Well, they astèd him, they questioned him,

O what stained his hands with blood?

O the answer he ‘plied back to they:

“Only the bleeding all from my nose.”

O then he went up to get to bed,

O no rest could ever Jackie take;

For out of belching flames of fire all round he flew,

All for murdering his own true love.

It were just a few days after that,

That poor innocent girl she were found;

She come floating by her mother’s door

What did live in old London Town.

O then that young man he was took and tried,

And oh, he was condemned to die;

He said, “My mother died while I were young,

O five children she left small:

Have mercy on me this day,

“For I’m the caretaker of the all.”

Spoken: Well, that’s a relegend - but ‘twas a love song.

Sarah Porter sings Down by the Deep River Side

(As) I strolled out one bright summer’s morn

Down by the deep river side

Who should I meet but a fair gentleman

And he asked me to be his bride

“O no sir, I am far far too young

I’m only sweet sixteen.”

“For the younger you are, sure the better that’ll be

For to spend that night with me.”

O the night rolling by and the morning soon came

The sun shone through the door

For this young man he rose, put on his clothes

And he bid, “Farewell my dear.”

“O this is not the promise that you made to me

Down by that deep river side

O you promised me that you’d marry me

For to make you my awful wife.”

“How can I marry a silly young girl

That’s only sweet sixteen.

You’d better go home to your mother’s house

For to drive those tears away.”

“How can I go back to my mother’s house

To show great shame and disgrace?

O before I’d go I’d drown myself

For to die in some lonesome place.”

Sure he catched hold of her by her lily white hand

He kissed both cheeks and chin;

He led her to the deep river side

Where he gently pushed her in.

See how she goes, see how she floats

A-floating away with the tide

’Stead of her having a watery grave

She had ought to been my bride.

Now there is off to some foreign land

Another flash girl for me.

There’s nobody knows the deed that I’ve done

To the girl I left behind.

Peter Bellamy sings The Prentice Boy

As I was fast bound ’prentice boy, I was bound unto a mill,

And I served my master truly for seven years or more,

Till I took up a-courting with that girl with the rolling eye,

And I promised I would marry her if she would be my bride.

So I went round to her parents’ house, it being the hour of eight,

And little did her parents think that it would be her fate.

And I asked her for to walk with me through the fields and meadows gay,

And there we told our tales of love and fixed the wedding day.

As we were a-walking and a-talking of these different things around,

I pulled a large stick from the hedge and I knocked this fair maid down.

Down on her bended knees she fell and loud for mercy cried,

“O have pity on an innocent girl, I am not fit to die.”

But I grabbed her by the curly locks and I dragged her on the ground

And I dragged her to the river Brigg that run through Ekefield town.

It ran both deep and narrow; it ran both swift and wide,

And there I plunged the pretty fair maid that should have been my bride.

So I went back to my parents’ house about ten o’clock that night.

And my mother she jumped out of bed all for to light the light.

She asked me and she questioned me, “What stains your hands and clothes?”

And the answer I gave back to her, “I’ve been bleeding at my nose.”

But no rest, no rest, all that long night; no rest, no rest, could I find.

For the fire and the brimstone around my head did shine,

And it was about two days afterwards this pretty fair maid was found,

A-floating by the riverbank that flowed through Ekefield town.

So the judges and the jurymen on me they did agree,

For a-murdering of this pretty fair maid a-hanged I will be.

O hanged, O hanged, O hanged I will be,

For a-murdering of this pretty fair maid a-hanged I will be

Jack Smith sings How Could I Marry

As I walked out one bright summer’s day

To view the country round,

Now who should I spy but a fair pretty maid,

O she fairly took my eye, my eye,

O she fairly took my eye.

She asked of me to marry her,

And make me her awful bride.

O the answer which I did give to her,

“O no, my love not I, not I,

O no, my love not I.

“How could I marry such a girl as you,

So easily led astray?

You’d better go back to your parents’ house,

And there you ought to stay, to stay,

And there you ought to stay.”

“Before I’d go back to my parents’ house,

To shame and disgrace myself,

I’d rather go down by the riverside,

And there to drown myself, myself,

And there to drown myself.”

No sooner the poor girl had spoken this,

He kissed her both cheeks and chin.

He put his arms round her middle so small,

And he gently pushed her in, her in

And he gently pushed her in.

See how she goes, see how she floats,

A-floating along by the tide.

Instead of her having a watery grave,

O she ought to been my bride, my bride,

O she ought to been my bride.

Going home to take his rest,

No rest nor peace could he find;

The spirit of that dear murdery girl

O she haunted him all night, all night,

O she haunted him all night.

Now I must go to some foreign land,

For another girl to find.

She will not know the deeds I have done

Or the girl I’ve left behind, behind,

Or the girl I’ve left behind.

Spoken: Now that’s a true song …

Shirley Collins sings The Oxford Girl

I fell in love with an Oxford girl

She had a dark and a roving eye.

But I feeled too ashamed for to marry her,

Her being so young a maid.

I went up to her father’s house

About twelve o’clock one night,

Asking her if she’s take a walk

Through the fields and meadows gay.

I took her by the lily-white hand

And I kissed her cheek and chin,

But I had no thoughts of murdering her

Nor in no evil way.

I catched a stick from out the hedge

And I gently knocked her down,

And blood from that poor innocent girl

Came a-trinkling to the ground

I catched fast hold of her curly, curly locks

And I dragged her through the fields,

Until we came to a deep riverside

Where I gently flung her in.

Look how she go, look how she floats,

She’s a-drowning on the tide,

And instead of her having a watery grave

She should have been my bride.

Lizzie Higgins sings The Butcher Boy

“My parents gave me good learnin,

Good learning they gave unto me,

They sent me to butcher’s shop

For a butcher’s boy to be.

“It was there that I met with a fair young maid

With the dark and a-rolling eyes,

And I promised for to marry her

On the month of sweet July.”

He went up to her mother’s house

Between the hours of eight and nine

And he asked her for to walk with him

Down by the foaming brine.

“Down by the foaming brine we’ll go,

Down by that foaming brine,

For that would be a pleasant walk,

Down by the foaming brine.”

But they walked it east and they walked it west,

And they walked it all alone,

’Til he pulled a knife from out of his breast

An he stabbed her to the ground.

She fell upon her bended knees

And for mercy she did cry,

Roarin, “Billy dear, don’t murder me,

For I’m not prepared to die.”

He’s taen her by the lily-white hand

And he’s dragged her to the brim,

And with a mighty downward push

He pushed her body in.

He went home to his own mother’s house

Between the hours of twelve and one.

Oh, little did his mother think

What her only son had done.

He asked her for a handkerchief

To tie around his head,

And he asked her for a candlelight

To show him up to bed.

No sleep, no rest could this young man get,

No rest he could not find;

For he thought he saw the flames of Hell

Approaching his bedside.

But the murder it was soon found out

And the gallows wes his doom,

For the murder of sweet Mary Ann

Lies where the roses bloom.

Mary Ann Haynes sings Wexford Town

There was a pretty girl in Wexford Town,

She fell in love with a miller boy.

O he asked her [to] go walking,

Through fields so sweet and green,

So they might walk and they might talk,

For to plan their wedding day.

O he pulled a hedge-stake from the hedge,

And he beat her to the ground.

“John,” says she, “have pity on me,

I’m not fit enough to die.”

Now when he got to his mother’s house,

It was at the break of day,

His mother woke and let him in,

By the striking of a light.

He asked him, cross-questioned him,

“Look at the blood-stains on your hands and clothes.”

The answer John, oh, he thought fit;

“Sir, it’s a-bleeding from my nose.”

Just a few days after

O this poor girl she was found,

A-floating by her mother’s door

O that led to Wexford Town.

This young man was taken up,

And he’s bound down in irons strong.

O there he did lay patient there,

For the murder he had done.

Albion Country Band’s Hanged I Shall Be

Now as I was bound apprentice, I was ’prentice to the mill,

And I served my master truly for more than seven year.

Until I took up to courting with a lass with that rolling eye

And I promised that I’d marry her in the month of sweet July.

And as we went out a-walking through the fields and the meadows gay,

O it’s there we told our tales of love and we fixed our wedding day.

And as we were walking and talking of the things that grew around

O I took a stick all out of the hedge and I knocked that pretty maid down

Down on her bended knees she fell and loud for mercy cry,

“O spare the life of an innocent girl for I’m not prepared to die.”

But I took her by her curly locks and I dragged her on the ground

And I throwed her into the riverhead that flows to Ekefield town,

That flows so far to the distance, that flows so deep and wide,

O it’s there I threw this pretty fair maid that should have been my bride.

Now I went home to my parents’ house, it being late at night.

Mother she got out of bed all for to light the light.

O she asked me and she questioned me, “What stains your hands and clothes?”

And the answer I gave back to her, “I’ve been bleeding at my nose.”

No rest, no rest all that long night, no rest there could I find

For there’s sparks of fire and brimstone around my head did shine.

And it was about three days after that this pretty fair maid was found,

Floating by the riverhead that flows to Ekefield town.

That flows so far to the distance, that flows so deep and wide.

O it’s there they found this pretty fair maid that should have been my bride.

O the judges and the jurymen all on me they did agree

For a-murdering of this pretty fair maid oh hanged I shall be.

Mary Delaney sings Town of Linsborough

I’m belonging to Dublin City,

And a city ye all know well.

My parients reared me tenderly

And brought me up quite well.

‘Twas near the Town of Linsborough

Where they bound me to a mill;

It was there I beheld with a comely maid

With a dark and rolling eye.

She promised me she’d marry me

And with her I dwell;

At twelve o’clock that very same night

When I entered her sister’s door.

“Come out, come out, my joy and fair maid

And take a walk with me,

And then we’ll sit and chat a while

And ’point our wedding day.”

‘Twas with his false and inluded tongue

He coaxed that fair maid out,

And ‘twas from the ditch he broke a stick

And he knocked that fair maid down.

She went down on her bare bended knees,

For mercy she loudly cried,

O saying, “Willie dear, do not murder me,

And I not fit to die.”

Then he catched her by those yellow locks

And drew her along the ground;

He catch her by the yellow locks

And drew her along the ground,

‘Til he drew her to a river

Where her body could not be found.

Returning home to his master’s house

At twelve o’clock that night,

Saying, asking for a candle

For to show himself some light.

His master boldly asked him,

“What stained your hands and clothes?”

Look how quick he made him an answer,

“I’m bleeding from the nose”.

He went into bed, no more was said,

Neither rest nor peace could find,

Only the murder of that fair young maid

Laid heavy on his mind.

Now he was arrested and taken

And tried in London Town.

And the villain, he was transported

And his reverence come home free.

Amy Birch sings He Pulled a Dagger

He pulled a dagger from his coat

and laid her down to the ground

And there the blood came a-trickling,

a-trickling from the wound

He grabbed her by her curly locks

and he dragged her to the stream

There he bade a-thinking

when at last he throws her in

He watched her float, yes he watched her float,

he watched her go down with the tide

Saying: That poor girl’s got a watery grave

when she ought to have been my bride.

He goes home to his master’s house,

twelve o’clock that night

His master rose and let him in

by a-striking of a light

He asked him and he questioned him

what had stained his hands and his clothes

And the answer that he gave to him

was the bleedings from his nose

It was a few days after

that poor young girl was missed

They took him on suspicion

for a-doing all of this

They sent him on to Newgate,

there to be tried for his life

For the murdering of that honest young girl

what ought to have been his wife

It was a few days after

that poor young girl was found

She came floating down the river

near by Wesley town

The judge and the jury

they set theirselves to agree

For the murdering of the honest young girl

and a hanged you shall be

Elizabeth Stewart sings The Butcher’s Boy

O ma parents they gaed tae me good learning,

Good learnin they gaed tae me;

They sent me tae a butcher shop,

A butcher boy tae be.

I fell in love wi a nice young lass,

She’d a dark and the rovin ee;

I promised that I’d mairry her,

If one nicht she wad lie wi me.

He had coorted her for mony’s a day,

Six lang months an mair;

But anither een had taen his ee,

And he wis tae dispair.

For Mary Anne wis wi bairn tae him,

“O Willie what will I dae?

For ma baby it will soon be born,

So will you mairry me?”

He went up to her mother’s house,

’Tween the hours o eight and nine;

He asked her for tae tak a walk,

Down by the river side.

They walkèd east and they walkèd west,

And they walkèd aa aroond;

Till he took a knifie oot his breist,

And he stabbed her to the ground.

She went upon her bended knee,

And for mercy she did cry;

O Willie dinna murder me,

And leave me here tae die.

He took her by the milk-white hand,

And he dragged her on her own;

Until they came to yon rushing stream,

And he plunged her body in.

He went up to his mother’s house,

’Tween the hours o twelve and one;

It’s little did his mither think,

What her only son hae done.

The question she did put to him,

“Why the blood stains on your glove?”

The answer he gave to her,

“It wis from a bloody nose.”

He asked her for a candle.

For to light him up to bed;

And likewise for a hankerchief,

For to tie aroond his head.

Nae peace nor rest could this young man get,

No peace nor rest could he find;

For he thought he saw the flames o hell,

Approachin in his mind.

Noo this young man has been taen an tried,

And the gallows it wis his doom;

For the murdering of sweet Mary Ann,

A flooer that wis in bloom.

John Kirkpatrick sings Ickfield Town

O as I was fast bound ’prentice boy, I was ’prentice to a mill,

And I served my master truly and never thought no ill,

Till I took up a-courting with a girl with a rolling eye,

O her beauty bright was my delight, she being so young and shy.

Well I promised I would marry her, and her I did beguile.

O I kissed her and I courted her until she proved with child;

Then I asked her if she’d take a walk through the fields and meadows gay,

So that I might tell her tales of love, and fix our wedding day.

And as we were walking and talking all the different things around,

O I drew a stick from out the hedge and knocked this fair maid down.

Down on her bended knees she fell, so loud for mercy cried,

“O come spare the life of a innocent girl, for I am not fit to die.”

I took her by the curly locks and I dragged her on the ground

I dragged her to the riverside that flows through Ickfield town.

O it runs both long and narrow; it runs both deep and wide,

And there I plunged this pretty fair maid that should have been my bride.

And then I went home to my parents’ house, it being so late at night.

O my mother she jumped out of bed all for to light the light.

She asked me and she questioned me, “O what stains your hands and clothes?”

And the answer I gave back to her, “I’ve been bleeding at the nose.”

No rest, no rest that live long night; no rest, no rest could I find.

The fire and the brimstone around my head did shine.

Look how she goes, look how she flows, a-floating on the tide;

Instead of having a watery grave she should have been my bride.

But it was about two days after, this fair young maid was found,

A-floating by the riverside that flows through Ickfield town.

O the judges and the jurymen on me they did agree,

For murdering of this pretty fair maid so hanged I shall be.

O hanged, O hanged, O hanged I shall be,

For murdering of this pretty fair maid, so hanged I shall be.

Waterson:Carthy sing The Oxford Girl

My parents said you catered me,

while learning they did give.

They bound me to apprentice,

A miller for to be.

Then I fell in love with an Oxford girl

With a dark and roving eye.

And I promised her I would marry her

If she with me would lie.

I courted her for six long months

A little now and then

Till I thought it a shame to marry her,

Me being so young a man.

And I asked her for to take a walk

Down by some shady grove

And there we walked and we talked of love

And we set a wedding day.

But I pulled a little stick from off the hedge

And struck her to the ground

Until the blood of that innocent

Lay trickling all around

Down on her bended knees she’d fall

And tearfully she’d cry,

“O Jimmy dear, don’t you murder me,

For I’m too young to die.”

So I went unto my master’s house

About the hour of night.

And my master rose and he let me in

By the striking of a light.

Well he asked of me and he questioned me,

“What stains your hands and clothes?”

Well I quickly made for to answer,

“Just the bleeding of my nose.”

No rest nor peace that night I find,

I do in torment lie.

For the murder of my own true love

Now I am condemned to die.

David Stacey sings Wexford Town

Now there was a pretty maid in Wexford Town

She fell in love with a miller boy

He asked her to go walking

Through fields so sweet and green

That they might walk, and they might talk

All for to name their wedding night.

But he took a hedge stake from the hedge

And he beat her to the ground.

“For mercy” cried, “I’m innocent,

I’m not fit enough to die.”

Now when he came to his master’s house

It being the middle of the night,

His master rose and let him in

By the striking of the light.

O he askèd him, cross-questioned him,

Saying “What are those blood stains

On your hands and clothes?”

The answer, O what he saw fit,

Was “Sir, it’s the bleeding from my nose.”

But it was just a few days after,

When her body it was found

A-floating past her mother’s door,

O what led to Wexford Town.

And now that young man’s taken up,

He’s bound down in iron strong

And now he do a prisoner

For the murder he have done.

Acknowledgements

The Albion Country Band lyrics were copied from the Ashley Hutchings songbook, A Little Music.